New Year wishes for a great year in 2014, with lots of interesting birding and dragonflying for all.

Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Saturday, December 21, 2013

White Christmas – Almost

We had some snow yesterday in Anacortes, so I thought I would do a Happy-face Darner Christmas card with a snowflake theme:

The snow is gone today, and unlikely to return anytime soon, so we just missed a white Christmas by a few days.

See another Happy-face Darner Christmas card here:

http://thedragonflywhisperer.blogspot.com/2013/12/christmas-is-coming.html

The snow is gone today, and unlikely to return anytime soon, so we just missed a white Christmas by a few days.

See another Happy-face Darner Christmas card here:

http://thedragonflywhisperer.blogspot.com/2013/12/christmas-is-coming.html

Friday, December 20, 2013

The Vitruvian Dragonfly

We're all familiar with da Vinci's Vitruvian Man, which explores the proportions of the human figure. Inspired by it, I decided to put together a version for dragonflies. Here it is, the Vitruvian Dragonfly:

This uses the stick figure I sketched some time ago. It's based on the Happy-face Darner, also known as the Paddle-tailed Darner, and is taken from a photo, ensuring that all the proportions are correct.

This uses the stick figure I sketched some time ago. It's based on the Happy-face Darner, also known as the Paddle-tailed Darner, and is taken from a photo, ensuring that all the proportions are correct.

Thursday, December 19, 2013

A Late Darner

This year featured a number of dragonfly species that were flying well beyond their usual flight season. One example of this is the Variable Darner. We see this species only occasionally at Cranberry Lake, and so it was a particular surprise to see one on October 29, nine days after the previous late flight date.

Here's the flight season of the Variable Darner in our area, including this new extension:

Notice that they start pretty late in the year, and go almost until November.

The next graph shows the Observation Percentage for the Variable Darner – that is, the percentage of all our observations of the Variable Darner that occur in a given month:

Over 60% of our observations occur in August. As you can see, observations of this species are rather sporadic.

The Variable Darner is widely distributed in North America, as indicated in the following dot map:

Here's its distribution in the Pacific Northwest, which is fairly uniform:

The male Variable Darner that visited up on October 29 is shown below. Notice the thin side stripes that actually break off into spots, the cream color on the 10th segment of the abdomen, and the simple appendages.

Another characteristic of this species is its propensity for perching on a wall or other flat vertical surface. In this case it landed on the vertical concrete wall of the dam at one end of Cranberry Lake. It's very common to see a Variable Darner perched in this way, but the other darners in our area generally land in bushes and trees.

Here's the flight season of the Variable Darner in our area, including this new extension:

Notice that they start pretty late in the year, and go almost until November.

The next graph shows the Observation Percentage for the Variable Darner – that is, the percentage of all our observations of the Variable Darner that occur in a given month:

Over 60% of our observations occur in August. As you can see, observations of this species are rather sporadic.

The Variable Darner is widely distributed in North America, as indicated in the following dot map:

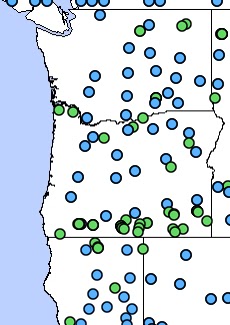

Here's its distribution in the Pacific Northwest, which is fairly uniform:

The male Variable Darner that visited up on October 29 is shown below. Notice the thin side stripes that actually break off into spots, the cream color on the 10th segment of the abdomen, and the simple appendages.

Another characteristic of this species is its propensity for perching on a wall or other flat vertical surface. In this case it landed on the vertical concrete wall of the dam at one end of Cranberry Lake. It's very common to see a Variable Darner perched in this way, but the other darners in our area generally land in bushes and trees.

Sunday, December 8, 2013

Christmas Is Coming!

We've started receiving Christmas cards, so I thought it would be a good time to send out greetings of the season from the Happy-face Darner to the readers of "The Dragonfly Whisperer" blog. Happy Holidays!

Saturday, November 30, 2013

Splash-Dunk Events For 2013

Well, the dragonfly season for 2013 is drawing to a close. We're still hoping to see an Autumn Meadowhawk one day, if the Sun comes out, but the darners are long gone, and with them the splash-dunks and spin-drys.

It's time, then, to collect the data for this year. Below is a chart showing the number of splash-dunk events seen this year as a function of the date of observation.

Notice the roughly "normal" distribution about the peak centered at September. I knew September was a good month for splash-dunking, but hadn't realized how much it stands out from the other months.

Notice the roughly "normal" distribution about the peak centered at September. I knew September was a good month for splash-dunking, but hadn't realized how much it stands out from the other months.

Most of the splash-dunk events were observed at Cranberry Lake, and most involved darners, like the Happy-face Darner (aka the Paddle-tailed Darner) depicted to the right. This is a "stick figure" I produced from a photo of a Happy-face – so the proportions are correct. I plan to use this image to illustrate "wing grabbing" when attaching in tandem, as well as other behaviors.

It's time, then, to collect the data for this year. Below is a chart showing the number of splash-dunk events seen this year as a function of the date of observation.

Notice the roughly "normal" distribution about the peak centered at September. I knew September was a good month for splash-dunking, but hadn't realized how much it stands out from the other months.

Notice the roughly "normal" distribution about the peak centered at September. I knew September was a good month for splash-dunking, but hadn't realized how much it stands out from the other months.Most of the splash-dunk events were observed at Cranberry Lake, and most involved darners, like the Happy-face Darner (aka the Paddle-tailed Darner) depicted to the right. This is a "stick figure" I produced from a photo of a Happy-face – so the proportions are correct. I plan to use this image to illustrate "wing grabbing" when attaching in tandem, as well as other behaviors.

Friday, November 15, 2013

I Looked For It

One of my favorite literary characters is Sherlock Holmes. I've often wondered what it would have been like if Holmes had taken up birdwatching instead of beekeeping. A birder with the sharp observing skills of Sherlock Holmes would be something to behold.

I can just imagine an exchange between Holmes and Watson going something like this:

Watson: Look Holmes, a Hutton's Vireo.

Holmes: If you look closely, Watson, I think you will find that it is actually a Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

Watson: Why do you say that Holmes?

Holmes: Elementary my dear Watson. Notice the yellow feet, the delicate bill, and the light wing bar with a distinct black border, all sure signs of a kinglet.

Watson: By Jove, Holmes, you're right. I just saw it flash its ruby crown.

The other day I had a chance to repeat a famous line from the Holmes canon in the context of dragonflying. It was fun. The line, basically, is "I looked for it," and it occurs in a couple Sherlock Holmes stories.

One example is in Silver Blaze, which is actually more famous for the following exchange:

Gregory (official police detective): "Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?"

Later in the story, Holmes lies on the ground and searches through the mud, finally finding a crucial clue – a small match.

"I cannot think how I came to overlook it," said the Inspector, with an expression of annoyance.

"It was invisible, buried in the mud. I only saw it because I was looking for it."

Ah, he looked for it. Exactly.

A similar exchange occurs in The Adventure of the Dancing Men. A key part of that adventure is a coded message written with dancing men, as follows:

At one point Holmes and a police inspector are investigating the scene of the crime when the following conversation ensues:

“… there are still four cartridges in the revolver," said the inspector. "Two have been fired and two wounds inflicted, so each bullet can be accounted for."

Indeed.

In my case, I was dragonflying at Cranberry Lake, when I saw a Happy-face Dragonfly in the bushes. It looked like this:

A man walking by saw me looking intently at the bushes. He stopped and asked, "What do you have there?"

"A dragonfly," I replied.

"Oh, really? Where is it?"

"Right here," I said, pointing into the bushes. It took some time to help him find it in the tangle of branches.

When he finally found it he stepped back, looked at me, and said, "How did you ever find it there?"

"I looked for it," I said.

|

| Sherlock Holmes in the field. Looking for birds? Dragonflies? |

I can just imagine an exchange between Holmes and Watson going something like this:

Watson: Look Holmes, a Hutton's Vireo.

Holmes: If you look closely, Watson, I think you will find that it is actually a Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

Watson: Why do you say that Holmes?

Holmes: Elementary my dear Watson. Notice the yellow feet, the delicate bill, and the light wing bar with a distinct black border, all sure signs of a kinglet.

Watson: By Jove, Holmes, you're right. I just saw it flash its ruby crown.

The other day I had a chance to repeat a famous line from the Holmes canon in the context of dragonflying. It was fun. The line, basically, is "I looked for it," and it occurs in a couple Sherlock Holmes stories.

One example is in Silver Blaze, which is actually more famous for the following exchange:

Gregory (official police detective): "Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?"

Holmes: "To the curious incident of the

dog in the night-time."

Gregory: "The dog did nothing in the

night-time."

Holmes: "That was the curious

incident."

Later in the story, Holmes lies on the ground and searches through the mud, finally finding a crucial clue – a small match.

|

| Holmes on the prowl for clues. |

"I cannot think how I came to overlook it," said the Inspector, with an expression of annoyance.

"It was invisible, buried in the mud. I only saw it because I was looking for it."

Ah, he looked for it. Exactly.

At one point Holmes and a police inspector are investigating the scene of the crime when the following conversation ensues:

“… there are still four cartridges in the revolver," said the inspector. "Two have been fired and two wounds inflicted, so each bullet can be accounted for."

“So it would seem,” said Holmes.

“Perhaps you can account also for the bullet which has so obviously struck the

edge of the window?”

He had turned suddenly, and his long, thin finger was pointing to a hole

which had been drilled right through the lower window-sash, about an inch above

the bottom.

“By George!” cried the inspector. “How ever did you see that?”

“I looked for it.”

In my case, I was dragonflying at Cranberry Lake, when I saw a Happy-face Dragonfly in the bushes. It looked like this:

|

| A male Happy-face Darner smiling up at me. |

A man walking by saw me looking intently at the bushes. He stopped and asked, "What do you have there?"

"A dragonfly," I replied.

"Oh, really? Where is it?"

"Right here," I said, pointing into the bushes. It took some time to help him find it in the tangle of branches.

When he finally found it he stepped back, looked at me, and said, "How did you ever find it there?"

"I looked for it," I said.

Monday, November 11, 2013

A Late Meadowhawk

On October 6, Betsy and I went to Magnuson Park in Seattle for a little dragonflying. We weren't expecting too much that time of year, but it was a nice day, and we thought we might as well give it a try. We found quite a few darners and spreadwings, as we expected, so it was a fun outing.

To our surprise, we also found some Cardinal Meadowhawks out and about. They are one of our first meadowhawks to appear. In fact, they show up in early May, well before most of the other common meadowhawks in our area. We hadn't expected to see them this late in the season, and a check with the calendar of flight dates showed that the latest date previously reported for the Cardinal Meadowhawk was October 2. Here's a look at the flight season for Cardinal Meadowhawks, including our modest extension to October 6:

Another way to look at the flight season is shown below. In this graph, we plot the probability a Cardinal Meadowhawk will be seen in a given month. For example, notice that about 40% of the Cardinal Meadowhawk observations are made in the month of July. The data for this plot are taken from 3 successive years of observations.

Even though it was late in the season, the Cardinal Meadowhawks were in prime color – which means intense red. Here are a couple photos from October 6:

Cardinal Meadowhawks are primarily a west coast species, as you can see from the following dot map:

Even in our part of the country, they tend to be more common in the west:

When identifying meadowhawks, remember that Cardinal Meadowhawks are our only meadowhawk with a dark red concentration of color near the base of the wings. This field mark can be seen from virtually any angle, which is often not the case for the white spots on the side of the thorax, and is quite definitive for this species.

To our surprise, we also found some Cardinal Meadowhawks out and about. They are one of our first meadowhawks to appear. In fact, they show up in early May, well before most of the other common meadowhawks in our area. We hadn't expected to see them this late in the season, and a check with the calendar of flight dates showed that the latest date previously reported for the Cardinal Meadowhawk was October 2. Here's a look at the flight season for Cardinal Meadowhawks, including our modest extension to October 6:

Another way to look at the flight season is shown below. In this graph, we plot the probability a Cardinal Meadowhawk will be seen in a given month. For example, notice that about 40% of the Cardinal Meadowhawk observations are made in the month of July. The data for this plot are taken from 3 successive years of observations.

Even though it was late in the season, the Cardinal Meadowhawks were in prime color – which means intense red. Here are a couple photos from October 6:

|

| A male Cardinal Meadowhawk. Notice the dark red color at the base of the wings. |

|

| Brilliant red on a sparkling, sunny day. The dark red in the wings is nicely visible, but the wings make it difficult to see the white dots on the side of the thorax. |

Cardinal Meadowhawks are primarily a west coast species, as you can see from the following dot map:

Even in our part of the country, they tend to be more common in the west:

When identifying meadowhawks, remember that Cardinal Meadowhawks are our only meadowhawk with a dark red concentration of color near the base of the wings. This field mark can be seen from virtually any angle, which is often not the case for the white spots on the side of the thorax, and is quite definitive for this species.

Wednesday, November 6, 2013

Cumulative Splash-Dunk Data

Betsy and I have been observing splash-dunks and spin-drys for the last few years. To date, we've observed 338 splash-dunk events, which we define as a case where a dragonfly (usually a darner) plunges into the water one or more times to clean itself. When we see an event, we count the number of successive splash-dunks that occur. The total number of splash-dunks we've observed is 780.

The maximum number of splash-dunks observed in a given event is 8 – at least, so far. This particular observation is described in the The Case of the Constipated Darner at the following link:

http://thedragonflywhisperer.blogspot.com/search/label/constipated

Here's a histogram of our combined results for 2011, 2012 and 2013:

The average number of splash-dunks per event (2.31) and the least-squares fit to an exponential have changed very little from last year's results. Here's the analysis of the data:

Overall, the drop off in the number of events is roughly exponential, though there appears to be a larger number of three splash-dunk events than one might expect – a bit of a "shoulder" in the data there. We'll see how these results evolve as more data is collected.

The maximum number of splash-dunks observed in a given event is 8 – at least, so far. This particular observation is described in the The Case of the Constipated Darner at the following link:

http://thedragonflywhisperer.blogspot.com/search/label/constipated

Here's a histogram of our combined results for 2011, 2012 and 2013:

The average number of splash-dunks per event (2.31) and the least-squares fit to an exponential have changed very little from last year's results. Here's the analysis of the data:

Overall, the drop off in the number of events is roughly exponential, though there appears to be a larger number of three splash-dunk events than one might expect – a bit of a "shoulder" in the data there. We'll see how these results evolve as more data is collected.

Saturday, November 2, 2013

A Six Meadowhawk Day

Last week, October 23 and 24, Betsy and I went to the Sun Mountain Lodge in Winthrop, WA to enjoy the Fall colors for a couple days. It was beautiful there, as you can see in these photos:

We went to the Beaver Pond, of course, but weren't expecting that much dragonfly activity. We would have been happy to see a few. As it turned out, the activity was very good, with lots of darners patrolling the shore looking for females, and meadowhawks flying in tandem over the water, dipping and laying eggs. In some areas, each step would flush several meadowhawks from the ground into the air. It was delightful. We had a six meadowhawk day, with the following species:

White-faced Meadowhawk

Striped Meadowhawk

Saffron-winged Meadowhawk

Band-winged Meadowhawk

Black Meadowhawk

Autumn Meadowhawk

A six meadow hawk day would be good in the summer, but was especially pleasant to experience this time of year. The most common species was the Saffron-winged Meadowhawk. We saw only one White-faced Meadowhawk, and it set a new record late date by 16 days. Here are pics of the meadowhawks:

As usual, we had a great time at the Sun Mountain Lodge and the Beaver Pond.

|

| Sun Mountain Lodge from our room. |

|

| The Fall colors were in full effect. |

|

| A Golden-crowned Kinglet gave me an opportunity for a quick snapshot. |

We went to the Beaver Pond, of course, but weren't expecting that much dragonfly activity. We would have been happy to see a few. As it turned out, the activity was very good, with lots of darners patrolling the shore looking for females, and meadowhawks flying in tandem over the water, dipping and laying eggs. In some areas, each step would flush several meadowhawks from the ground into the air. It was delightful. We had a six meadowhawk day, with the following species:

White-faced Meadowhawk

Striped Meadowhawk

Saffron-winged Meadowhawk

Band-winged Meadowhawk

Black Meadowhawk

Autumn Meadowhawk

A six meadow hawk day would be good in the summer, but was especially pleasant to experience this time of year. The most common species was the Saffron-winged Meadowhawk. We saw only one White-faced Meadowhawk, and it set a new record late date by 16 days. Here are pics of the meadowhawks:

|

| White-faced Meadowhawk. |

|

| Striped Meadowhawk. An older individual with frayed wings and faded stripes. |

|

| Saffron-winged Meadowhawk on the left, and Band-winged Meadowhawk on the right. |

|

| Black Meadowhawk. We don't see Black Meadowhawks all that often, so this one was a particular treat. |

|

| Autumn Meadowhawk. One of the "field marks" for Autumn Meadowhawks is that they land on you. |

As usual, we had a great time at the Sun Mountain Lodge and the Beaver Pond.

Wednesday, October 2, 2013

The Dragonfly Whisperer Speaks Again!

It's not too soon to make plans for the upcoming Dragonfly Whisperer Talk to be given at the Prescott Audubon Society's general meeting on May 22, 2014. They've been kind enough to invite me to speak, and I'm looking forward to it.

They have a very active organization, with lots of different programs, and they've produced some excellent promotional materials to advertise the talk. As an example, here's an ad they'll distribute next April:

That should attract some attention.

Their website contains more specific information:

Looks like a good talk! Betsy and I will be there – be sure to say "Hi" if you can make it too.

You can find more information about Prescott Audubon at the following website:

http://prescottaudubon.org

They have a very active organization, with lots of different programs, and they've produced some excellent promotional materials to advertise the talk. As an example, here's an ad they'll distribute next April:

That should attract some attention.

Their website contains more specific information:

Looks like a good talk! Betsy and I will be there – be sure to say "Hi" if you can make it too.

You can find more information about Prescott Audubon at the following website:

http://prescottaudubon.org

Friday, September 27, 2013

Darner Hovering: Bobbing With Bursts

Hovering is an energy-intensive activity. It's not surprising, then, that dragonflies might employ strategies to reduce the effort – or at least rest the muscles a bit. Here's an example.

I was observing a Happy-face Darner (Paddle-tailed Darner) hovering at Beaver Pond in Winthrop, WA. As it hovered, I noticed it was bobbing up-and-down in a regular manner. This might not seem surprising, considering that its wingbeats don't provide constant lift. The frequency of the "bobbing" motion was much smaller than the frequency of the wingbeats, however. The wings beat at about 35-40 beats per second, whereas the bobbing motion was clearly only a fraction of that frequency. I decided to record a video to study the hovering in more detail.

Here's one of the videos I recorded. It's recorded in "real time"; that is, normal speed.

A better view can be had at the following link to the Dragonfly Whisperer Channel on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8oLKmfMLBc

As you can see, the wings are beating so fast they're just a blur. In contrast, the body bobs up-and-down at a much slower rate.

I made frame-by-frame measurements of the flight level of the darner from the video and have plotted the results below.

The data show a clear periodicity to the flight level. The darner is indeed bobbing up-and-down with quite a well-defined frequency.

The bobbing motion has a period of about 0.2 s, which corresponds to 5 bobs per second – or roughly one bobbing cycle for every 8 wingbeats. The angular frequency of this motion, w, is about 31 radians per second, and the amplitude, A, is about 0.4 cm. It follows that the maximum upward and downward acceleration is roughly Aw^2 = 3.8 m/s^2, which is just under 40% of the acceleration due to gravity. Thus, the darner is never in free fall; it's always getting lift from the wings, but the lift varies with a period of 0.2 s.

It seems, then, that the darner alternates weaker and stronger wingbeats as it hovers, a little like the flight of finches and woodpeckers. This is indicated in the plot below. With this strategy, the darner can give a burst of 4 strong wingbeats, rest for 4 wingbeats, give another burst of 4 strong wingbeats, rest for 4 wingbeats, and so on. Perhaps the intermittent rest helps it hover for long periods of time without getting fatigued.

I was observing a Happy-face Darner (Paddle-tailed Darner) hovering at Beaver Pond in Winthrop, WA. As it hovered, I noticed it was bobbing up-and-down in a regular manner. This might not seem surprising, considering that its wingbeats don't provide constant lift. The frequency of the "bobbing" motion was much smaller than the frequency of the wingbeats, however. The wings beat at about 35-40 beats per second, whereas the bobbing motion was clearly only a fraction of that frequency. I decided to record a video to study the hovering in more detail.

Here's one of the videos I recorded. It's recorded in "real time"; that is, normal speed.

A better view can be had at the following link to the Dragonfly Whisperer Channel on YouTube:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r8oLKmfMLBc

As you can see, the wings are beating so fast they're just a blur. In contrast, the body bobs up-and-down at a much slower rate.

I made frame-by-frame measurements of the flight level of the darner from the video and have plotted the results below.

|

| Data from a video showing the up-and-down bobbing motion of a hovering darner. |

The data show a clear periodicity to the flight level. The darner is indeed bobbing up-and-down with quite a well-defined frequency.

The bobbing motion has a period of about 0.2 s, which corresponds to 5 bobs per second – or roughly one bobbing cycle for every 8 wingbeats. The angular frequency of this motion, w, is about 31 radians per second, and the amplitude, A, is about 0.4 cm. It follows that the maximum upward and downward acceleration is roughly Aw^2 = 3.8 m/s^2, which is just under 40% of the acceleration due to gravity. Thus, the darner is never in free fall; it's always getting lift from the wings, but the lift varies with a period of 0.2 s.

It seems, then, that the darner alternates weaker and stronger wingbeats as it hovers, a little like the flight of finches and woodpeckers. This is indicated in the plot below. With this strategy, the darner can give a burst of 4 strong wingbeats, rest for 4 wingbeats, give another burst of 4 strong wingbeats, rest for 4 wingbeats, and so on. Perhaps the intermittent rest helps it hover for long periods of time without getting fatigued.

|

| Same plot as above, but with times of weak and strong wingbeats indicated. |

Monday, September 23, 2013

Darner Mating Behavior: Attaching In Tandem

All dragonflies and damselflies mate in the so-called "wheel" or "heart-shaped" position. In this position, the tip of the male's abdomen grabs the female behind the head in dragonflies, or on the front of her thorax in damselflies, and the tip of the female's abdomen attaches to the base of segment 2 of the male's abdomen. A good example in the Common Green Darner is shown below:

The first step in attaining this position is for the male to grab the female and attach his abdomen to her, forming a tandem pair. The following is a slow-motion video (1/4 speed) showing this attachment process in the Happy-face Darner (Paddle-tailed Darner):

A better quality video can be seen on the Dragonfly Whisperer YouTube Channel at the following link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_ap7Aex9Y4

What's particularly interesting about this process is the way the male grips the female tightly as he makes the attachment. Notice how the rear legs of the male slip down behind the female's forewings and pull them forward, folding them tightly against her thorax. The male holds her like this for a moment as he shudders rapidly – apparently acquiring the desired connection – and then releases her wings and tries to take off. In this case the female doesn't cooperate, and the male eventually gives up and departs alone.

I hadn't known before that the male folds the wings forward like that when it attaches in tandem. It seems like quite an extreme maneuver. You often see females with large tears in the forewings, and I wonder how often the tears are the result of this behavior. This particular female had a large tear on the left forewing, as you can see in the photos below:

When the male pulls the forewings forward you can see that his leg fits nicely into that tear. Before this video I might have considered the tear to be the result of a bird attack, but I think another possibility must be considered.

The other interesting feature of this video is the male's rapid oscillation of his abdomen (about 60 oscillations per second) just before he tries to take off. Is he making sure he's got a good attachment? I found one reference to something like this in Corbet, Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. On page 276 he describes a male Common Green Darner that is in tandem when it's attacked by another male. According to Corbet, "the tandem male shakes its abdomen in a convulsive movement detectable to the human observer only when portrayed in slow motion." I wonder if this is the same basic behavior.

|

| Common Green Darners in the wheel position during mating. |

The first step in attaining this position is for the male to grab the female and attach his abdomen to her, forming a tandem pair. The following is a slow-motion video (1/4 speed) showing this attachment process in the Happy-face Darner (Paddle-tailed Darner):

A better quality video can be seen on the Dragonfly Whisperer YouTube Channel at the following link:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p_ap7Aex9Y4

What's particularly interesting about this process is the way the male grips the female tightly as he makes the attachment. Notice how the rear legs of the male slip down behind the female's forewings and pull them forward, folding them tightly against her thorax. The male holds her like this for a moment as he shudders rapidly – apparently acquiring the desired connection – and then releases her wings and tries to take off. In this case the female doesn't cooperate, and the male eventually gives up and departs alone.

I hadn't known before that the male folds the wings forward like that when it attaches in tandem. It seems like quite an extreme maneuver. You often see females with large tears in the forewings, and I wonder how often the tears are the result of this behavior. This particular female had a large tear on the left forewing, as you can see in the photos below:

|

| Notice the large tear just behind the nodus (bend) in the left forewing. |

When the male pulls the forewings forward you can see that his leg fits nicely into that tear. Before this video I might have considered the tear to be the result of a bird attack, but I think another possibility must be considered.

The other interesting feature of this video is the male's rapid oscillation of his abdomen (about 60 oscillations per second) just before he tries to take off. Is he making sure he's got a good attachment? I found one reference to something like this in Corbet, Dragonflies: Behavior and Ecology of Odonata. On page 276 he describes a male Common Green Darner that is in tandem when it's attacked by another male. According to Corbet, "the tandem male shakes its abdomen in a convulsive movement detectable to the human observer only when portrayed in slow motion." I wonder if this is the same basic behavior.

Wednesday, September 18, 2013

Autumn Has Arrived!

Well, not according to the calendar – for a few days yet – but as far as the dragonflies are concerned it has. Recall the following haiku:

Red dragonfly on my shoulder,

calls me his friend.

Autumn has arrived.

The Autumn Meadowhawks are out in numbers at Cranberry Lake, and they are landing on your shoulders, arms, legs, shoes, etc. In fact, you have to be careful where you step to make sure you don't step on one or more of them. Here are a few pictures from Cranberry Lake last year to give you an idea of what it's like there now:

The Autumn Meadowhawk has been named the world's friendliest dragonfly by DASA, the Dragonfly Appreciation Society of America (membership consists so far of Jim and Betsy Walker).

The darners are also present in numbers right now. The sunlit bushes at the lake were hosts to 6 to 8 perched darners at any given time, mostly Paddle-tailed Darners, but also a couple Shadow Darners and a Variable Darner.

Update:

The next day we made our first observation of a Dark-eyed Junco in our backyard. This is another species whose occurrence is linked with the seasons – we see them on or close to the first day of Fall, they stay with us all winter, then disappear again around the first day of Spring. They are extremely accurate, usually to within a day or two, as they were again this year.

Here's a little haiku to commemorate their appearance:

Dark-eyed Junco in my yard,

hopping to and fro.

Autumn has arrived.

Red dragonfly on my shoulder,

calls me his friend.

Autumn has arrived.

The Autumn Meadowhawks are out in numbers at Cranberry Lake, and they are landing on your shoulders, arms, legs, shoes, etc. In fact, you have to be careful where you step to make sure you don't step on one or more of them. Here are a few pictures from Cranberry Lake last year to give you an idea of what it's like there now:

|

| A pair of Autumn Meadowhawks in the wheel position on my finger. |

|

| The Autumn Meadowhawks are fairly numerous, and they seek out perching sites with good exposure to the sun. |

|

| Dragonfly on the shoulder – and the hat, too! |

The Autumn Meadowhawk has been named the world's friendliest dragonfly by DASA, the Dragonfly Appreciation Society of America (membership consists so far of Jim and Betsy Walker).

The darners are also present in numbers right now. The sunlit bushes at the lake were hosts to 6 to 8 perched darners at any given time, mostly Paddle-tailed Darners, but also a couple Shadow Darners and a Variable Darner.

Update:

The next day we made our first observation of a Dark-eyed Junco in our backyard. This is another species whose occurrence is linked with the seasons – we see them on or close to the first day of Fall, they stay with us all winter, then disappear again around the first day of Spring. They are extremely accurate, usually to within a day or two, as they were again this year.

Here's a little haiku to commemorate their appearance:

Dark-eyed Junco in my yard,

hopping to and fro.

Autumn has arrived.

Friday, September 6, 2013

Band-winged Meadowhawk

On a recent field trip to Burke Lake near Quincy, Washington, we saw a number of Band-winged Meadowhawks. Here's a young female that posed for its picture, happy to be a part of the Dragonfly Whisperer blog:

This meadowhawk is named for the band of amber color near the base of the wings. When I first started dragonflying, it was called the Western Meadowhawk, and there was a similar species in the eastern U. S. called the Band-winged Meadowhawk. These species have been merged due to the fact that intermediates were found. They all go by the name Band-winged Meadowhawk now.

Band-winged Meadowhawks seem very finicky about where to land. They often hover above a perch, and just when it looks like they're going to land they lift off again, only to come back for another try. This can happen numerous times before they finally "take the plunge" and settle down on the perch. Here's another view of this species from Burke Lake, showing the bands in the wings a little more clearly:

This is dragonfly is widespread across the northern part of North America, as can be seen in the following dot map from Odonata Central:

|

| Band-winged Meadowhawk (female). |

This meadowhawk is named for the band of amber color near the base of the wings. When I first started dragonflying, it was called the Western Meadowhawk, and there was a similar species in the eastern U. S. called the Band-winged Meadowhawk. These species have been merged due to the fact that intermediates were found. They all go by the name Band-winged Meadowhawk now.

Band-winged Meadowhawks seem very finicky about where to land. They often hover above a perch, and just when it looks like they're going to land they lift off again, only to come back for another try. This can happen numerous times before they finally "take the plunge" and settle down on the perch. Here's another view of this species from Burke Lake, showing the bands in the wings a little more clearly:

This is dragonfly is widespread across the northern part of North America, as can be seen in the following dot map from Odonata Central:

Here's a closer look at the dot map for the Pacific Northwest area:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)